As an 18-year-old volunteer ambulance driver for the American Red Cross in World War I, Ernest Hemingway’s whimsical notion of combat and sense of invincibility were shattered the instant an Austrian mortar shell hit his dugout. The attack killed two Italian soldiers and left Hemingway’s body riddled with fragments across his foot, knee, thighs, scalp and hand. He spent the next six months recuperating in an Italian hospital before he could be sent home.

Despite his serious injuries, Hemingway’s war experience bore some silver linings. The adrenaline junky fulfilled his patriotic duty, met his first wife and found inspiration for two short stories: “Soldier’s Home” and “Big Two-Hearted River.” So when German U-boats began patrolling the Caribbean waters around Cuba in WWII, Hemingway threw caution to the wind again and embarked on an adventure crazier than any story he ever wrote.

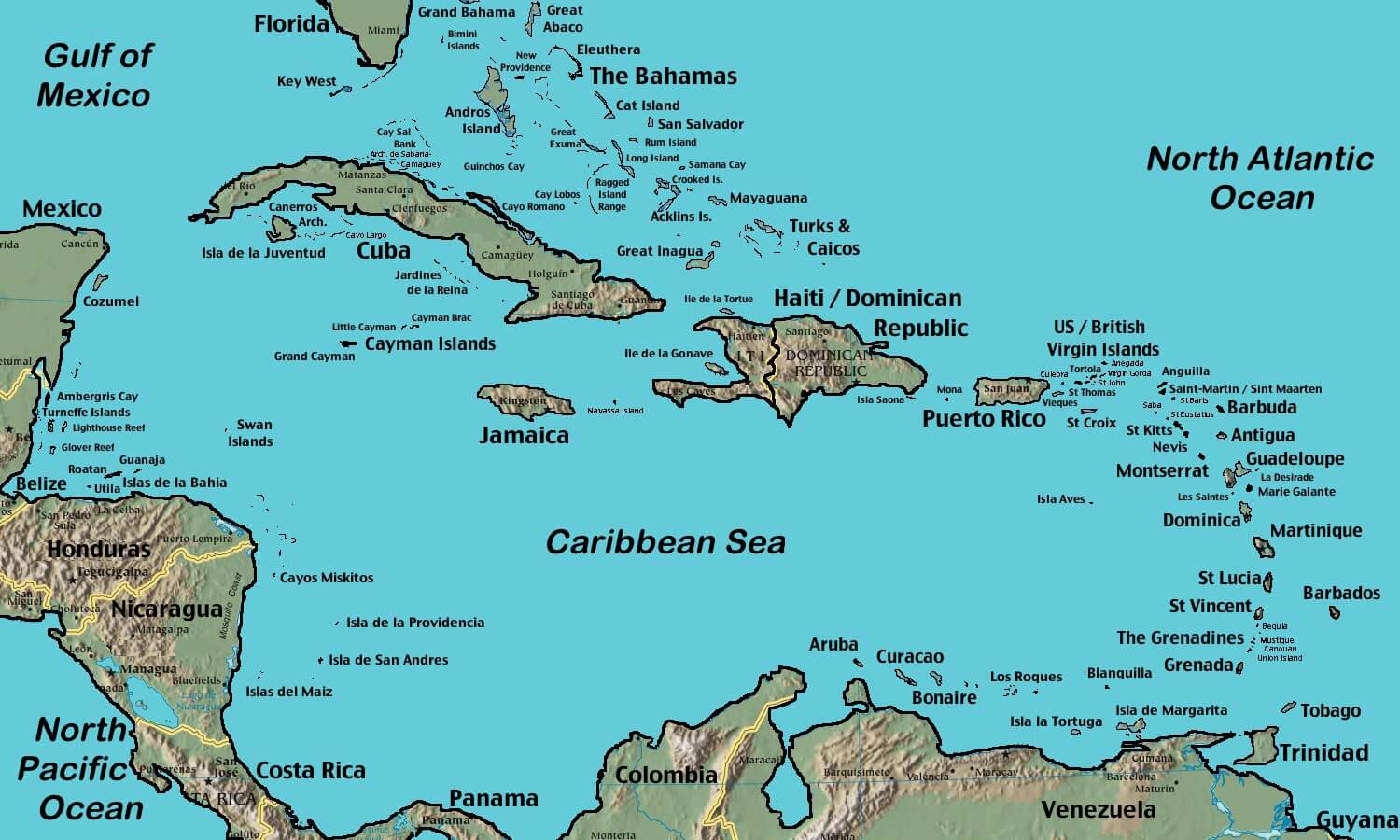

WWII Comes to the Caribbean

Planes, tanks and combat machinery all require one key input — oil. In the 1940s, the U.S. produced 60 percent of the world’s crude oil; however domestic oil supplies had to be shipped thousands of miles to reach the battlefields in Europe.

Stop the tankers. Squeeze the supply. Win the war. That was Germany’s plan.

And the strategy was working. Over the course of the war, U-boats sent 148 petroleum tankers to watery graves in the Gulf of Mexico and along the East Coast. America needed to protect its major oil ports as well as its shipping routes to ensure the steady flow of oil supplies.

In the spring of 1942, the Allies were losing about 15 boats a month to U-boat attacks in Cuban waters. With wars in both the European and Pacific Theaters and resources stretched thin, the U.S. Navy implored local yachters to outfit their boats with weapons and help patrol the waters for U-boats. Hemingway jumped at the chance to snag his biggest catch ever — Nazis.

Pilar Goes to War

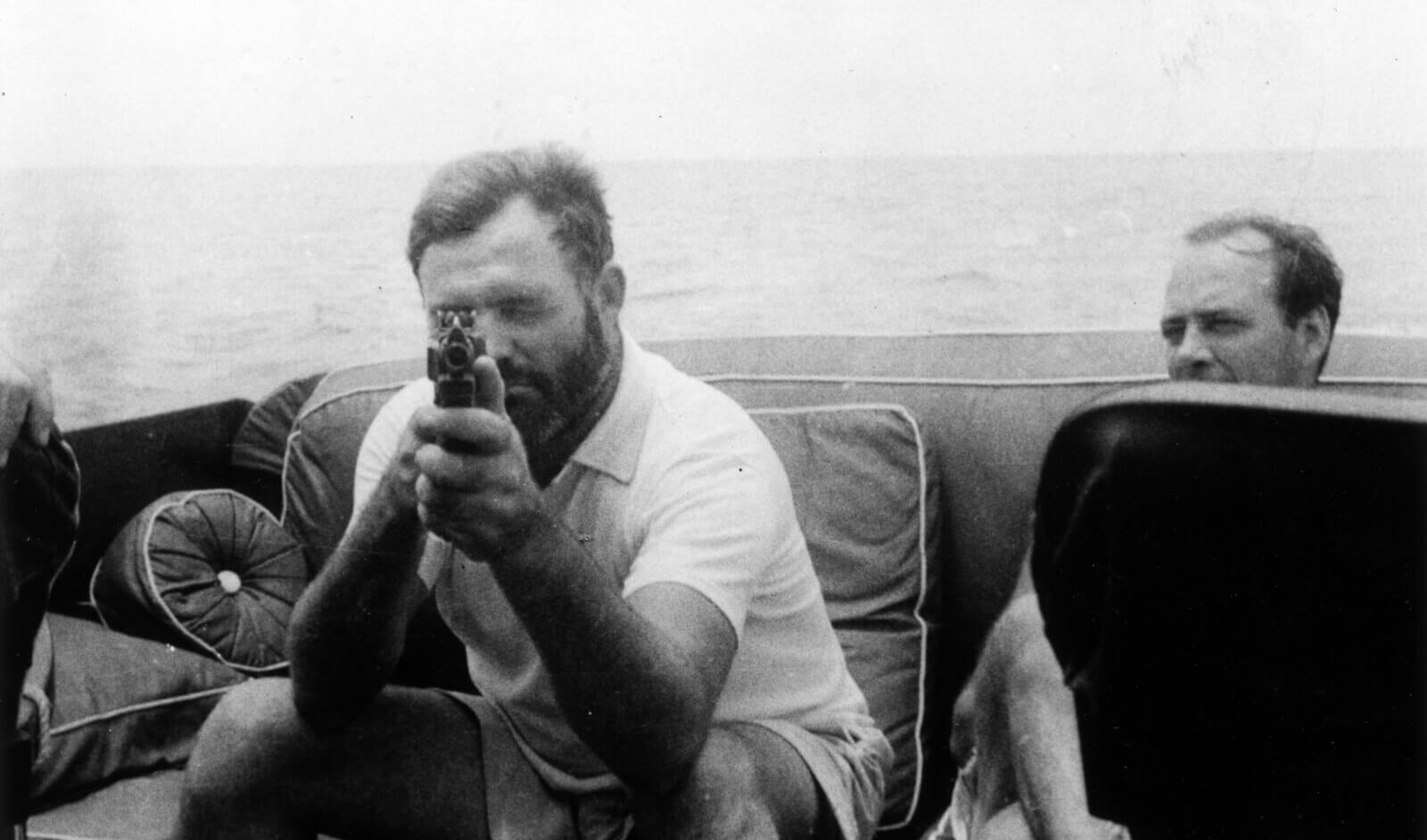

Hemingway owned a customized, wooden 38-foot Wheeler Yacht named Pilar, and he was very eager to lend a hand to the Navy. The military armed his crew with light machine guns, bazookas and grenades, and a specially made bomb that sat atop the flybridge.

The plan was to pose as a fishing vessel to lure U-boats to the surface, then fire rounds at the unsuspecting crew and toss the bomb into the enemy vessel’s conning tower. Hemingway’s men believed the element of surprise would enable them to either kill or capture the U-boat’s crew and possibly even nab a valuable German codebook.

Pilar set out on daily patrols of the Caribbean Sea lanes and ventured into isolated cays where U-boats were sometimes known to hide out or pick up supplies left by sympathizers. Hemingway even made his U-boat hunt a family affair. During the summer months, his 11-year-old son Gregory and 14-year-old Patrick were invited aboard Pilar and stood guard with rifles as they prowled the open water.

Hemingway and wife Mary aboard the Pilar

Covert Military Operation or Fish Tale?

Back in Cuba, Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, was skeptical of his U-boat escapades. She viewed the crew’s maritime shenanigans as an excuse to get scarce wartime fuel so they could fish, get drunk and hurl grenades at buoys.

Dubbed “Operation Friendless,” Hemingway initially approached his mission with the fervor of an infantryman. He was brazenly self-assured his wooden ship could take down a 214-foot-steel boat equipped with deck guns and torpedoes.

But what Hemingway had in confidence, he lacked in tactical planning. Most U-boats stayed submerged during the day and only surfaced at night. Pilar only patrolled while the sun was up and it lacked sonar or radar to detect the subs, making Hemingway’s hunt a total shot in the dark.

The days grew long, and the action was almost non-existent. Logging lengthy reports for the Navy became tedious for Hemingway and eavesdropping on U-boat radio communications was futile since no one on the crew spoke German.

Fish (Almost) On

Despite spending the better part of a year hunting U-boats, Hemingway only had one potential sighting in 1943 while his sons were aboard. From 1,000 feet away, the crew suspected a vessel to be a surfaced U-boat. Hemingway ordered everyone to grab their weapons and take their positions. They even unmoored the bomb on the flybridge in case they got close enough to hurl it down the ship’s conning tower. Pilar gave chase and the assumed U-boat sped away, leaving Hemingway and his crew apoplectic they’d missed their chance to encounter the Germans.

By July of 1943, enthusiasm for Pilar’s mission had dwindled as much as the crew’s booze supplies. Hemingway received a coded message ordering Pilar back to Cuba and she returned to port, worse for the wear after many months at sea. Attacks in the Caribbean Sea were winding down and the crew’s lofty ambitions at subterfuge were over.

Hemingway never captured an elusive U-boat, but he did find inspiration. He parlayed his experience into “Islands in the Stream,” a novel about an American artist turned sub chaser in the Caribbean during WWII. Just like his mission, the book went unfinished during his lifetime. Hemingway’s fourth wife, Mary, stumbled upon the manuscript and had it published posthumously to grace the world with Hemingway’s reimagining of the high-stakes adventure he wished he’d had.