After embarking on an African safari in 1934, world-famous author Ernest Hemingway returned to New York City to pick up a $3,300 advance from Esquire magazine. With the sizable check in hand, the seasoned adventurer didn’t go to a bank or even his favorite watering hole. Instead, he drove straight to the Wheeler Shipyard in Brooklyn, NY to put a down payment on what would become one of the greatest loves of his life — his customized Playmate yacht, Pilar.

Founded by Howard E. Wheeler in 1910s, the Wheeler Yacht Company had a national reputation for the exceptional quality and craftsmanship of its wooden boats. As an avid fisherman, Hemingway collaborated with Wesley L. Wheeler, the family’s naval architect, and his team to modify the standard 38-foot Playmate model to include extra-large fuel tanks for staying at sea longer and an icebox. He also wanted the aft section of the deck to be cut down by 12 inches to allow better access to the fish. And he wanted the hull to be painted black, like the rum runners of the day.

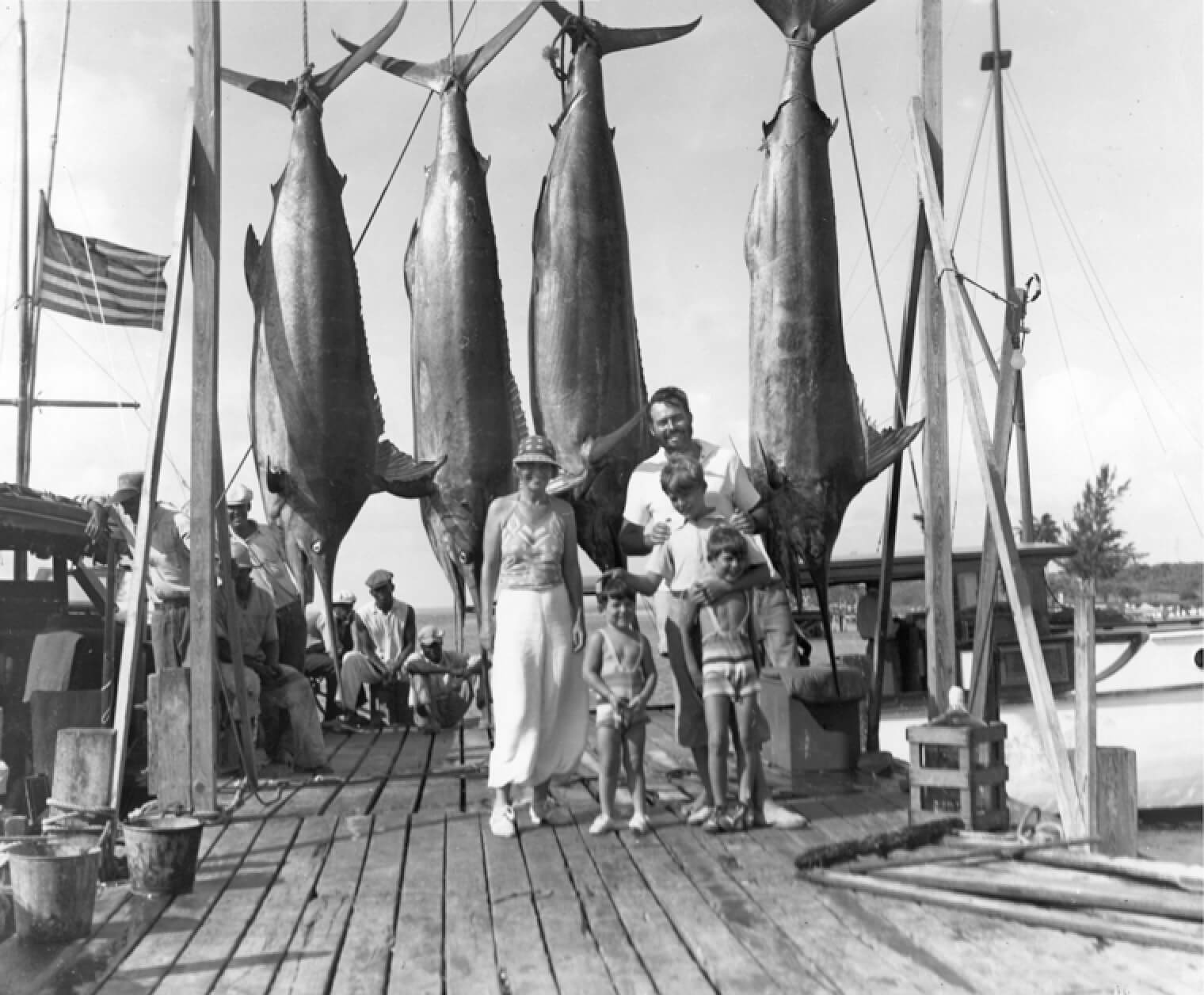

Ernest, Pauline, Bumby, Patrick, and Gloria Hemingway in 1935

Pilar carried a phonograph, a Philmor radio and his typewriter. It slept six and had two engines — one for trolling, the other for cruising at a top speed of 16 knots. The final price tag on the custom, black-hulled yacht came to $7,455, nearly $170,000 in today’s dollars. Hemingway had the boat shipped to Merrill Stevens Boat Yard in Miami where he christened her Pilar after his then-wife, Pauline. Overtime, Hemingway further customized Pilar with a flybridge, a wooden roller spanning the transom to help haul fish aboard, a fighting chair and bamboo outriggers to assist in his fishing escapades.

Ernest and Pauline divorced in 1940, and later that same year he married Martha Gelhorn. The new couple relocated to Cuba and bought Finca Vigia, a home on a hilltop overlooking Havana. Unbeknownst to Hemingway, when he docked his beloved Pilar in Cojimar, a small fishing village east of the capital, it would inspire one of his most critically acclaimed works of fiction.

Troubled Waters

Hemingway was one of the most prolific and successful writers of the 1920s and 1930s, but by 1950, he had gone nearly 10 years without publishing a novel. His four marriages, war correspondence and adventurous exploits in big-game hunting and fishing were legendary with the press, but despite his notoriety, he found himself questioning how he could preserve his art in the face of fame and attention. When he published “Across the River and Into the Trees” in 1951, it was panned by critics and generally considered one of the biggest literary disasters of his career.

Gone Fishing

Upon settling in Cuba, Hemingway met Gregorio Fuentes who became Pilar’s captain, and subsequently his friend, bartender and confidante. The two men enjoyed countless exploits hooking, reeling in, and gaffing large bluefin tuna, broadbill swordfish and blue marlin over Pilar’s stern. Sometimes their fishing expeditions would last for three days straight, allowing the fish more time to bite and for Hemingway to clear his head.

Aboard Pilar, Hemingway learned all about Fuentes’ life story. Born in the Canary Islands, the Spaniard earned his sea legs at the age of 10 as a deck boy for his father. In his teens, he worked on cargo ships out of the Canary Islands to Trinidad and Puerto Rico, and from the Spanish ports of Valencia and Sevilla to South America. By 22, he had immigrated to Cuba to work as a fisherman, where decades later he would cross paths with Hemingway.

Penning a Classic Aboard Pilar

As Hemingway stewed over the reception of his last failed novel, he found inspiration in Fuentes and began funneling his displeasure and creativity into an allegory for his own struggles. With a typewriter on the starboard side of the cockpit next to his favorite radio, Hemingway spent the next eight weeks pouring his heart into the pages of “The Old Man and the Sea.”

The book tells the tale of Santiago who was once a great fisherman but becomes a laughingstock after going 84 days without a catch. Much like Hemingway felt compelled to prove himself in the literary world again, Santiago went in search of a great fish to seek redemption.

Sailing beyond the shallow coastal waters, Santiago takes his skiff into the Gulf Stream in search of bigger, more valuable fish. He hooks a giant marlin, and an epic battle ensues to reel him in over the next three days.

The themes of failure and perseverance, strength and pain, solidarity and religion are woven throughout the allegorical tale. In the end, Santiago perseveres over the marlin and tethers it to his small boat to bring it back to his fishing village. Anticipating book critics would tear apart this work, Hemingway’s protagonist is unable to fend off sharks from his prized marlin and Santiago returns to shore with only a skeleton in tow.

On the day Hemingway finished writing “The Old Man and the Sea,” he wrote his publisher and declared the book the best writing he had ever done. This instinct turned out to be spot on. Hemingway’s novella about finding purpose and contentment in life’s struggles resurrected his flailing reputation. The book won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1953, became one of his bestselling works and turned Hemingway into an international celebrity. And he did it all aboard his muse, a 38’ Wheeler Playmate yacht named Pilar.

Pilar Today

Hemingway described Pilar as his “one true thing” in his life, a companion who outlasted three wives and countless friendships. When Mary and Ernest Hemingway left Cuba in 1960 amid a spate of executions by the Castro regime, they had every intention of returning to their home. History however, had other plans.

In 1961, the Bay of Pigs Invasion failed to overthrow Fidel Castro’s communist government, solidifying the dictator’s power and further souring U.S.-Cuba relations. Knowing he could not return to the island nation and retrieve his beloved Pilar, Hemingway was shattered.

The loss of his boat was a devastating blow to the author who relied on Pilar as his refuge for escaping bad reviews and broken relationships. After years of intense physical pain and crushing depression, Hemingway took his own life later that year.

After Hemingway’s death, his widow gave Pilar to a man who also loved the boat, her captain, Gregorio Fuentes. Not wanting to continue sailing it without Hemingway, Fuentes donated it to the Cuban government.

Around that same time, Finca Vigia, the couple’s home, was expropriated by the government and later turned into a museum to honor Hemingway’s legacy. Today, keepsakes from the author’s incredible life are on display throughout the property — from books to hunting trophies to his most prized possession of all: Pilar, which sits on Hemingway’s tennis court as a museum. It has survived several hurricanes over the years and has been lovingly restored for all to see.

More than 80 years later, the great-grandson of Howard Wheeler and grandson of Pilar’s architect, Wesley P. Wheeler, was granted special permission to tour the inside of Finca Vigia and board Pilar to confirm her authenticity on behalf of the Wheeler family. He took detailed measurements to reverse engineer the ship, and today Pilar lives on as a Wheeler 38 with its new name, Legend. The re-birth of Pilar now sits majestically in Slip No. 1 in the Harbour Town Yacht Basin on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.